The Eighties Club

The Politics and Pop Culture of the 1980s

|

"Rather in Tiananmen Square"

from

Anchors: Brokaw, Jennings, Rather and the Evening News

Robert Goldberg & Gerald Jay Goldberg (New York: Birch Lane Press, 1990)

|

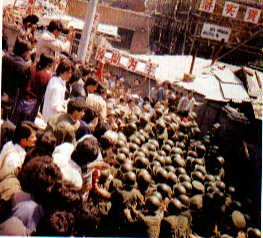

Protesters blocking the army's advance into Tiananmen Square

Recently, TV journalism has undergone a major shift. Today, there's a new emphasis on foreign coverage. The startling events of the past year, in places as far-flung as Beijing and Berlin, have certainly played a huge role in this development.

If foreign news is expensive, nothing is more expensive than sending the anchor himself on the road, with his standard traveling entourage of fifty to one hundred reporters, producers, cameramen and technicians. But about two years ago, Rather, Jennings and Brokaw began regularly uprooting themselves from their studio settings to broadcast live from locations around the globe.

This change actually started in earnest near the end of 1988, with CBS's summit coverage from Moscow (including their prize-winning series of reports from the USSR entitled "Inside the Kremlin"). In early January 1989, CBS and ABC sent their anchors to Emperor Hirohito's funeral in Japan. Covering diverse aspects of Japanese society, Rather and Jennings presented a rich tapestry of information to their viewers.

The live transmissions used by all three networks from Japan were nothing new. The capacity to do these live "remotes," as they were called, had been in existence for over two decades, although for years it was infrequently used, mostly for conventions and space shots. But within the past two years a new idea had been percolating at the networks: There's nothing like getting the feel of a place, and nothing does that better than having an anchor on the scene.

Of course, anchors would never have left their studios had they not been driven out by network competition and aided by technological improvements. It was technology that made it possible to go on the road, to air a live broadcast from anywhere on earth. "We're much more capable of going to an unscheduled event live than five years ago," says ABC senior producer Steve Tello. "The technology has improved so greatly." There have been communications satellites orbiting the earth for thirty years . . . , but uplinks were generally not available unless one went to the government station.

The flyaway satellite dish has changed all that. "The flyaway dishes are smaller," says Tello, "and they break down to fit into fifteen to twenty suitcases. They fit on commercial airplanes, even smaller planes." The technicians simply open the cases, reassemble the parts and voila!, a ready-made satellite uplink.

Given this open and much larger stage, all three networks, of course, want to dominate it. Live international coverage has become the sine qua non, the latest measuring stick in a brutally competitive environment. Today when a story breaks anywhere on the planet, there is no substitute for the network news anchor being there live. Technology makes it possible. Competition makes it inevitable.

Following President Bush on his way back to the U.S., the CBS team covered his brief visit to China. Having heard some vague rumors about a mounting sense of discontent in China, Rather and producer Harry Radliffe headed off into the Beijing streets to see what they could find. They had been told about the People's Purple Bamboo Park. There was a corner of the park where students and intellectuals -- people who wanted to practice their English -- would gather. Apparently groups were coming together in increasingly large numbers to talk about democracy and freedom. They decided to bring a camera to the park, to see if there wasn't a story in it for the "Sunday Evening News."

"We went over," Rather recalls, "and we hadn't been there five minutes when he looked at me, and I looked at him, and . . . we knew. We knew that what was happening below was beginning to break through the surface. You could hear it, you could sense it. You just knew."

On the flight home that evening, Rather and [executive producer Tom] Bettag thought and plotted and schemed about how they could get back to China.

They knew this would be an extremely tough sell back at West 57th Street. After all, they had just spent nearly $3 million on Japan. And now China? How could they possibly convince [president of CBS News] David Burke, and more importantly, the overseer of the entire CBS operation, the bottom-line oriented Larry Tisch, to lay out even more money on this kind of gamble?

When Burke took the China proposal to Tisch . . . he had to sell hard. Rather helped with the pitch. Tisch went along with the plan, but according to sources, with a caveat. He'd write the checks if they went over budget this time, but come the next fiscal year, they'd get no such break. They would have to stick to budget, no matter what. That seemed fair enough to Burke. And as for Rather, given the green light, he was elated.

But up to the last minute . . . Rather wondered if they were making a mistake. The week they were scheduled to leave for China, the Panama story broke. Manuel Noriega had initiated the bloody beating of opposition vice-presidential candidate Guillermo "Billy" Ford, and then had stolen the election. President Bush had ordered thousands of additional troops to the Central American state.

When they arrived in Beijing on Saturday morning, May 13, they paused only long enough to drop their bags at their hotel, the Shangri-la. The hotel was a strange place, its decor a surreal mix of East and West. In the lobby, Chinese musicians dressed in tuxedos played Brahms. The Shangri-la would serve as the base of operations for the CBS team of sixty to seventy. On the fifth floor, beds had been moved out of the rooms to create work spaces for tape editing equipment, assignment desks and correspondents writing rooms. In fact, there was even a control room. Down in the Pagoda Garden, a camera position for reporter stand-ups had been created. All in all, says [special events director] Lane Venardos, "we built a studio from scratch at the Shangri-la."

The anchor and his executive producer headed directly for Tiananmen Square, where students were beginning to congregate in large numbers. There were so many people milling around that it was already hard to get into the area.

Tiananmen Square, the vast open space just in front of the Forbidden City, has long been considered the heart of Beijing, the heart of China. It was here that emperors handed down their edicts, here that Mao Zedong announced the triump of his Communist revolution forty years earlier. And it was here that 100,000 students and hundreds of hunger strikers had massed to proclaim a new revolution, a revolution for democracy.

Over the next few days, the China story blossomed from news into history. Events would more than match Rather's extravagant language. ("After four days on hunger strike in this exposed, wind-swept area, students are dropping from exhaustion, some now are vowing to die if necessary.")

By Wednesday, the scale was truly awesome. Reporting from Tiananmen Square, Rather described how China's student protest had been transformed into a mass movement: "The world's largest public square has now become the scene of the biggest demonstration in the history of Communist China. It is Thursday morning here, the dawn of day six of a hunger strike for 3,000 students, but the whole character of the protest changed today, as scores of organized groups, including workers, poured in to join the rally. At its height, the crowd numbered more than a million . . . . The government no longer even pretends to control this area."

Powered by the sheer excitement of witnessing major news unfolding, Rather and his crew were in action more or less around the clock. Out in Tiananmen Square, the CBS team was broadcasting from what it euphemistically termed a "mobile unit." It consisted of two vehicles: a flatbed truck and a ten-year-old beat-up Jananese panel truck, a Toyota that Rather termed "a reject from a demolition derby." The Toyota was stuffed with equipment it was never designed to handle. Jerry-rigged on top of the flatbed was a camera and a tripod on one end. Rather himself was broadcasting standing on the other end. After a few days, the top was so slippery that Rather's tech team built him a small platform out of wooden crates.

In most of the twenty-four hour cycles that Rather and his team worked in China, he estimates they were doing up to a dozen different broadcasts. As the pace got even more frantic toward the end of the week, they did some forty-odd broadcasts (including cut-ins and brief spots for affiliates) in one twenty-four-hour cycle.

By the end of the week, the story had turned spectacular. By late afternoon, it was clear that hard-line moves were being planned by the government. All demonstrations would be banned by midnight. The square was filled with rumors of army units on the move. Rather went on the air and described the situation this way:

"Midnight: The deadline passes. More reports and rumors of troop movements, many close by.

"12:30 AM: Premier Li Peng appears in radio and television, speaking to an audience of top officials, and over loudspeakers to the crowds. He says anarchy and riots are threatening the state, threatening to wreck the economy. He blames it on a small group of conspirators trying to overthrow Communist rule. He declares a kind of martial law to put down the protest. Those listening on loudspeakers jeer and chant, 'Li Peng come down! Li Peng come down!'

"2:00 AM: The army still hasn't arrived. Truckloads of strike supporters begin coming in again. The students dare to hope.

"4:00 AM: Reports increase that the army has tried to move closer, but has run into passive resistance from the students . . . .

"By dawn's early light, the students were still here. They had won the night."

That optimism would prevail for a while. But only a few hours after Rather signed off on the live news broadcast, the government made its first move. Rather, Bettag and their team were still in the square, still operating from their beat-up Toyota truck, when the helicopters came.

"We thought it would only be a matter of time until they tried to cut off our broadcast," Rather recalls, "and by the second time the helicopters appeared, they had cut off the broadcast."

To understand what happened next, you have to visualize the electronic hook-up. Rather and his team were operating from Tiananmen Square out of their beat-up Toyota. The Japanese truck was loaded with equipment that would transmit audio and video via a microwave "hop" to a dish on top of a nearby hotel, where it would be relayed to their base camp at the Hotel Shangri-la. From there, the sound and pictures could be fed up to the satellite and back to New York. But nothing could be fed live out of China that didn't go to the satellite dish at the Shangri-la.

For Rather and his team in the square, the first indication of trouble came when the picture hook-up with the Shangri-la was cut. Someone was dismantling the microwave relay. Not too long after that, the audio was cut too.

Not knowing how long it would take them to get back to the Shangri-la through the crowds of students and hordes of troops, Rather and Bettag decided they would shoot off some last video tape, and get the hell out of there.

Army units were already stationed outside the Shangri-la, and although none of them seemed to have any specific orders, large groups were milling around ominously, shouldering their rifles. Rather, Bettag and their crew dashed inside the Pagoda Garden courtyard, where their basic broadcast position had been set up, looking for the CBS crew. Absolutely no one was there. In fact, there wasn't even a camera left in the courtyard.

Fearing the worst, they went sprinting up the five flights of stairs. Dashing down the corridor and rounding the corner, they stumbled onto a bizarre scene. In the dimly lit fifth floor hallway, in the middle of all sorts of equipment packing crates, Lane Venardos, director of Special Events coverage, a witty, rotund, Humpty-Dumpty figure, was locked in a tedious harangue with two ill-at-ease young Chinese bureaucrats in shirtsleeves.

"We've heard nothing from the foreign ministry," Venardos was saying. "We're authorized to be on the air until 0100 hours . . . ."

Down the hall, Susan Spencer provided running voice-over commentary on the surreal scene outside her door. "The Chinese government has apparently decided to impose a news blackout on a situation over which it has no control . . . . They have told us that all satellite transmissions must be stopped."

Rather launched himself into the middle of the group, shaking hands with the Chinese, and simultaneously checking the camera positions.

As he described the scenes out in the street -- martial law, students surrounding trucks and offering flowers to soldiers -- powerful lights went on, illuminating Rather, his sporty blue polo shirt, his safari jacket. Bettag handed him a note saying "You're live."

Across America, a bright red "CBS News Special Report" sign flashed up on screens in living rooms from coast to coast, and this feisty debate suddenly appeared in the middle of CBS's 10:00 PM Friday show, "Dallas." Viewers expecting to see J.R. were suddenly confronted with a battle at once more mundane and more mythic -- Dan Rather wrangling with two Chinese officials about his right to broadcast. It was a classic freedom of speech showdown between a reporter and a repressive government. On and off, it ran for a memorable half hour.

In a strange, doppleganger situation, Rather was at once negotiating with the Chinese to stay on the air, and providing running play-by-play commentary on these negotiations for viewers as he went along. "We've been operating in good faith . . . ." said Rather to the Chinese, then turned to the viewers: "All this against the backdrop of Deng Xiaopeng and Li Peng trying to exert authority over the country, and it's clear that they simply couldn't take our coverage . . . They shut us down at Tiananmen Square and they're trying to shut us down here."

Meanwhile, there was a new piece of video to be relayed. It was the first scene of violence, demonstrators being beaten by police with nightsticks, students with blood on their faces and hands.

Turning back to the camera, Rather announced one last piece of video tape with his characteristic verbal flourish, half awkward, half elegiac, at the end: "These are final pictures of . . . considerable chaos in downtown Beijing. These are the last pictures we'll be showing to you through our own facilities. And if we're able to show any more at all, I know not when . . . . This is Dan Rather, CBS News, Beijing."

And saying that, he turned to the heavyset technician manning the satellite controls, who flipped the switch.

And then the screen went black.

|