The Eighties Club

The Politics and Pop Culture of the 1980s

|

"The Neighborhood"

from

The Cocaine Kids: The Inside Story of a Teenage Drug Ring

Terry Williams (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing, 1989)

|

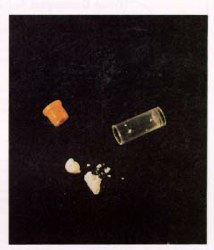

Two "rocks" and a crack cocaine vial.

Washington Heights stretches north on the west side of New York City from about 154th Street to 190th. In 1957, when Max's parents moved into the Heights, they were one of the first Dominican families to do so. Broadway, which runs north and south, was a dividing line: few Latinos and no African-Americans were allowed to rent apartments east of Broadway; few whites lived to the west.

It was truly a color line, says Mel, an African-American who works at a garage on 153rd Street. "You had those light, damn near white Cubanos who lived here and there during that time. Now we call Broadway 'Dominican Avenue.' This area was all Jews, some Irish, and some Italians. They had a couple Spanish clubs like the Pan American Club on 157th Street and Cabarrojeno on 145th. Some Spanish would come to the clubs but it didn't mean they come into the neighborhood to live, because clubs is one thing, and living in an apartment around here is something else."

Certainly it is true today that, although many different ethnic groups call Washington Heights home, Dominicans shape the character of this vibrant community. On a summer afternoon the streets are teeming with Latino noises, smells and talk. Men -- restaurant workers, street hustlers, store clerks, maintenance workers -- gather to play dominoes or cards or shoot dice in the shade of a barbershop awning or a faded sign above la groceria. There is Astroni's, always serving breakfast, lunch and dinner: young dealers and customers go there to make phone calls; police officers drive up in the small hours for coffee take-out.

Saturday morning around 9:00 is a quiet time for the neighborhood drug trade, but vendors of other street merchandise are busy spreading their wares on the sidewalk and most of the regular businesses -- Julio's Head Shop, Charlie's Metro Bar, the Greek-owned coffee shop, and many eateries -- are always open. In the Monarch Bar you can tell the dealers by the beepers clipped to their belts and by the way they handle money: they don't simply take out one bill to pay, but display the entire wad, counting off the bills in rapid strokes.

Along 156th Street, the house numbers signal the entranceways to many of the cocaine and crack houses in the area. Dealers like Jake stand cocksure in the doorways with their hands across their chests, luring customers -- they are only a short walk from the subway stop -- into the hallways. "Gypsy cab" drivers who have stopped to drink beer and snort a little perico talk near the barbershop; some are playing a favorite local card game, veinte-y-uno, twenty one. With money stacked high and every player eyeing the cash, they slam cards down with a cry loud enough to stop any passerby.

Micro-enterprises fill the street: men and women of all ages hawking shirts, hats, pocket calculators, watches, radios, handbags, jewelry, food, all without protest from storekeepers who seem willing to grant their compadres an equal opportunity to make money. A worn graffito across the base of a nearby building reads: GOD BLESS AMERICA AND THE YANKEE DOLLAR, and that seems to be the creed underlying the economic bustle of legal and illegal businesses.

Illegal transactions are a leading activity here, and hustling is the name of the game. One sign of this is the large number of secondary operations catering to the drug trade: candy stores that sell drug paraphernalia and head shops that sell little else, such as Perran's, across the street from one of New York's most active copping zones, its display window filled with an assortment of lactose, dextrose, mannitol (all used to adulterate cocaine) and a host of water pipes for smoking crack or marijuana. Perran's is open 24 hours, and, like many businesses in the area, is thriving.

Less visible are bootleggers who sell a local version of corn whiskey popular among cocaine users, the cocaine bars frequented by local dealers and users day and night, and the after-hour spots, a community institution, that also survive on the cash spent by cocaine habitues.

Cocaine also occupies a central place in the lifeways of this community in another, invisible sense: Salsa, Latin jazz or the Spanish language have never received wide acceptance in the United States, but cocaine surely has. As coca and cocaine are, after all, Latin in origin, there is some nationalistic pride mixed with the Dominican and Latin entrepreneurial drive here.

Yet in a way drug dealing is no more the focus of this community than the recent influx of Korean-owned businesses. This is a lively multi-ethnic community with family-run grocerias and liquor stores, check-cashing agencies, banks, restaurants, discos, hardware stores and so on. Boricua College, the newest institutional and cultural addition to the neighborhood, is the most recent tenant in the landmark McKim and White building at 155th Street, which also houses the American Indian Museum and the Hispanic Society as well as the Numismatic Society, The Geographic Society and the Society of Arts and Letters.

Across the street, the Church of the Intercession, the oldest church in Washington Heights, has programs for youth, for teenage pregnancy, AIDS prevention, and a strong interest in making this a better place to live. Nearby, Esperanza (Hope) Center, a community-based organization, helps new arrivals adjust to life in New York City, assist in landlord-tenant disputes and family problems, helps find jobs for youth and provides basic education for adults.

But here, too, despite the protests of many residents, teenagers and adults alike have taken to crack in unprecedented numbers -- as in other cities, large and small. Washington Heights, which the police call a "hot spot," is a battleground in the war on drugs. And as in all wars, it is the young who are the first casualties.

La oficina is located right in the middle of this bustling, mixed Washington Heights neighborhood. It has a large steel door specifically designed to prevent the police from knocking it down before the kids could dispose of the drugs. Chillie has hired the fourteen-year-old son of the building superintendent as a "catcher" -- he is on call to retrieve any cocaine thrown out the window during a bust. The stock or "stash" of cocaine is kept in a bag stitched with beads worn by adherents of Santeria (a set of religious practices involving Roman Catholic and African elements), and the boy's parents will not touch it because they fear it contains evil spirits. Chillie pays the boy in cash and cocaine.

The office is a small, one-bedroom apartment. A newcomer who enters the living room will see only a sofa, two chairs, a stereo, a TV, a tiny stool and some plants. Business hours are usually 1:00 PM to 5:00AM, six days a week. The three office workers are Charlie, the armed door guard, Masterrap, who acts as host and receives requests from buyers, and Chillie, the man behind the scale, who sets prices, arranges to barter goods and services, gives credit and makes day-to-day decisions regarding sales.

At la oficina, unlike many "coke houses," the scales, packaging material and the drug itself are not immediately visible. Chillie prefers to deal from the thickly-carpeted bedroom, with a full-sized platform bed, a desk, and a large walk-in closet filled with candles, coconuts, beads in water-filled jars, coins in large bowls, cigars, and a silver plate holding food and money. The desk and telephone, the center of operations, sit near one window, facing the door. In the middle of the desktop are aluminum foil packets evenly cut to wrap the cocaine, and a triple-beam scale. No cocaine is visible until the buyer has shown his money.

Chillie arranges for me to sit where I can observe clearly. He says I can come into the bedroom with some buyers, but not all, as some are "funny about that." "If anybody asks who you are, tell them it's none of their mother-f______ business. Just play past that shit." And for the next several hours, I sit in the living room with customers, talking with Masterrap or watching TV, until Chillie calls them. Few customers talk with Charlie -- as the guard, he refuses to engage in any conversation while he is on duty.

Once in a while, the buyers are friends, and Charlie or Masterrap will negotiate with Chillie on their behalf. Chillie pays a bonus for every buyer they bring in, ranging from a few dollars on gram or half-gram sales to $100 for a one-ounce sale.

The phone rings constantly. Chillie answers from his room, and in a few minutes the doorbell rings. The first buyer today is a young Spanish woman who speaks halting English. She calls for Chillie to come out and meet her, they embrace and kiss. He asks how much she wants to buy and they go into his room. The slide on the scale makes tiny noises as it moved along the ribbed bar. Ten minutes later she departs, after (he tells me) giving him $60 for a gram.

The doorbell rings again. Masterrap gets up and hollers "Back" to Charlie, who walks over and stands behind him. Masterrap peers into the peep hole; "it's cool," he announces, and Charlie relaxes and goes to sit in the kitchen. Two teenage Dominicans come in, wearing sneakers, leather jackets, and gold chains, and brand new blue jeans. Masterrap goes into a rap about music with them, then goes in to get them a taste from Chillie. They snort a bit, "take a freeze" (place a pinch of cocaine on the tongue), chat another minute or two, then go in to see Chillie.

After they leave, Masterrap and I talk about a movie we've both just seen. Charlie is in the kitchen, eating and yelling commands at a dog who is tied down. The dog, an akita ("They used to guard the emperors of Japan"), has a long curled tail, a strong face, and, though attentive, does not appear vicious or at all concerned with the goings-on. "They be mean dogs if you train them right," Charlie insists, lifting a piece of bread so the dog will jump for it. "Hey, they are better than them pit bulls out there," he asserts as if looking for an argument. When the dog moves about, Charlie shouts, "calmate, calmate," and it sits, head held high. Some time later, Chillie shot the dog because it ate two ounces of cocaine mistakenly left on the table.

In all, I see fifteen buyers come and go that afternoon. Each one tastes the cocaine before purchasing; none stays more than twenty minutes. The first buyer is the lone woman. Masterrap explains, "You know we have plenty of females coming in here not just to cop but to hang out. Chillie don't go for that all the time. We gotta limit it. If things are slow we let them stay longer or we might call a freak [a girl without inhibitions] to come over."

Buyers would say how much they wanted to purchase, and, after learning the price, would ask for discounts. Most sales were in the $60 to $80 range (1985). After the last customer, Chillie came out of the bathroom crowing, "I am The Deal-Maker."

|