The Eighties Club

The Politics and Pop Culture of the 1980s

|

"The Culture of Triumph and the Spirit of the Times"

from

Culture In an Age of Money: The Legacy of the 1980s in America

Nicolaus Mills, ed. (Chicago: Elephant Paperbacks, 1990)

|

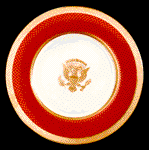

The Reagan White House china,

by Lenox, was a gift from the Knapp Foundation

In early 1981, as the Reagan administration was getting under way, its first cultural controversy began. Nancy Reagan wanted new china for the White House. The cost of the china was the problem. The Lenox pattern with a raised gold presidential seal in the center that the president's wife chose came to $209, 508 for 220 place settings. At a time when her husband was talking about cutting welfare eligibility and the misery index (inflation plus unemployment) was over 20 percent, Nancy Reagan's desire for new china seemed like an idea borrowed from Marie Antoinette.

Democrats rubbed their hands in glee. What they failed to understand was that a new era was starting. American culture in the 1980s would be a culture based on triumph -- on the admiration of power and status -- and nothing would be more important to that culture than its symbols. Especially at the start, they were what allowed the president to insist, "We have every right to dream heroic dreams."

The America that the Reagan administration inherited was an America still in shock from a decade of humiliation. The country had lost the longest war in its history. A president had resigned in disgrace. The economy was in shambles. Only a quarter of the voting-age population felt the government could be trusted to do what was right most of the time. New White House china would not erase these past humiliations, but like the president's pledge "to make America proud again," new china would be a start in the right direction.

During his final year in office, Jimmy Carter had talked about the country's "malaise." But for the Reagans, triumph would be the watchword. "The cynics were wrong. America never was a sick society," Ronald Reagan declared. In the 1980s his America would not look or act like a weakling nation. The president and his guests would eat off china that proclaimed, "The era of self-doubt is over." The demeaning humility of a Jimmy Carter, who allowed Iran to hold Americans hostage for 444 days and insisted he liked peanut butter sandwiches, was past.

....Money words -- yuppie, upscale, privatization, takeover -- became the key language of the 1980s, and they signaled a culture with an insatiable need to proclaim its triumphs. Even more important, especially after the Nixon-Ford-Carter years, they signaled a culture that was coherent in its promise. In the culture of triumph, the past was modern because it held the key to the future. Image was crucial because we needed to see ourselves afresh. Getting rich was justified because it left the nation better off. Cutting aid to the poor was humane because welfare hurt initiative.

A century earlier, government helped pave the way for the Gilded Age by ending both the inheritance tax and the income tax. In the 1980s the Reagan administration moved in a similar direction, cutting personal taxes and establishing Justice Department guidelines that all but ended antitrust activity. Businesses and individuals were given the green light to create the kind of America Ronald Reagan had in mind when he declared, "What I want to see above all is that this remains a country where someone can always get rich." It didn't take long for the green light to be noticed. "Conspicuous consumption," Gilded Age critic Thorstein Veblen's phrase for the ostentation of the leisure class, became in the 1980s "flaunting it." For a figure like real estate mogul Donald Trump, it was not enough to be seen in all the right places. It was essential to brand the world one occupied: to live in Trump Tower, to fly Trump Shuttle, to sail on the Trump Princess.

In Liar's Poker, an account of his days on Wall Street in the 1980s, Michael Lewis described his work at Salomon Brothers as occurring in the center of a modern gold rush. "Never have so many unskilled twenty-four-year-olds made so much money in so little time as we did in this decade," Lewis wrote. He was not indulging in hyperbole, not in a decade in which Drexel Burnham Lambert executive Michael Milken made $550 million in one year. On Wall Street the culture of triumph was king, and the key to it was the creation of a paper economy in which the buying and selling of companies was more profitable than running them. For the "hot" brokerage firms, ethics became irrelevant. Shortly before filing for bankruptcy in 1990, Drexel Burnham Lambert paid its executives $350 million in bonuses -- almost as much as it owed its creditors. And even among conservative brokerage houses, new rules and a new psychology reigned.

The 1980s became the decade in which the hostile takeover was made possible by the leveraged buyout and the junk bond, when greenmail was paid to avoid a takeover, when companies were attacked by raiders and saved by white knights, when fired executives floated into retirement on golden parachutes. Only a cynic or the special interests (labor unions, the civil rights movement) would oppose such a culture....

In foreign policy the most dramatic indication of the new culture of triumph was reflected in the revival of an imperial America committed to showing its power. Between 1980 and 1987 the military budget more than doubled, climbing to $282 billion annually. But the real change was in the country's inner psychology, its abandonment of what Ronald Reagan called our "Vietnam syndrome." The Grenada invasion of 1983 showed how serious the president was when he insisted Vietnam "was, in truth, a noble cause."....We were no longer a helpless giant. It was...clear what the president meant when during the 1980 campaign he declared, "There is a lesson for us all in Vietnam...let us tell those who fought that war that we will never again ask young men to fight and possibly die in a war that our government is afraid to let them win."....After Grenada it became easier to reimagine Vietnam as a war that America could have won. No longer did the Vietnam vet have to be a 1970s figure like the sensitive, crippled hero John [sic] Voight played in Coming Home. The vet of the 1980s could be Sylvester Stallone's John Rambo, whose rage and muscularity argue that we did not lose Vietnam on the battlefield, and who, on going back to rescue his POW buddies, asks the perfect Reagan question, "This time do we get to win?"

The domestic equivalent of Rambo was the Wall Street buccaneer, the takeover artist that financier Asher Edelman sought to cultivate in his Columbia Business School course "Corporate Raiding -- The Art of War," when he offered a $100,000 bounty to any student who found a company he could acquire. The real economic hero of the culture of triumph was. however, the dream consumer, the yuppie. It was the yuppie lifestyle that the Reagan administration had in mind when it adopted the Laffer curve, which said that if tax rates, especially at the upper level, were lowered, the rich would try to get even richer and in so doing improve the economy and government revenues.

There were, of course, jokes about the materialism of yuppies and their passion for brand names. But the yuppie was someone the 1980s culture quickly learned to love. As the popular television sitcom Family Ties showed, the yuppie was the button-down kid who knew the path to the good life. His 1960s baby-boom parents might not understand his ambitions, but they could not help being impressed (particularly when he was as likeable as Michael J. Fox's Alex Keaton) with how good he was at looking out for number one.

....For Reagan and the culture of triump, the extravaganza...became the crucial public event of the 1980s. Nothing else so clearly dramatized what both were about or showed what the president meant when he said, "When I spoke about a new beginning, I was talking about much more than budget cuts and incentives for savings and investment. I was talking about a fundamental change...that honors the legacy of the Founding Fathers."

The first inauguration with its $8 million price tag for four days of delebration set the tone for the extravaganzas that followed. It began with an $800,000 fireworks display at the Lincoln Memorial, followed by two nights of show-business performances presided over by the Reagans, and finally, on the fourth day, nine inaugural balls which conjured up the image of an American Versailles. From Almaden Vineyards came 14,400 bottles of champagne. From the Society of American Florists $13,000 worth of roses. From Ridgewell's caterers 400,000 hors d'oeuvres. "When you've got to pay $2,000 for a limousine for four days, $7 to park, and $2.50 to check your coat at a time when most people in the country can't hack it, that's ostentation," Senator Barry Goldwater groused. Goldwater had missed the point. The extravaganzas of the 1980s, like the culture of triumph, were not concerned with the work ethic of small-town America. They were advertisements for America the Grand, and their aesthetic, as Reagan-era historian Sidney Blumenthal shrewdly observed, was one in which the beautiful was the expensive, the good was the costly.

The inaugural aesthetic was repeated at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles. The president did not attend the games, instead contenting himself with urging the American team to "Do it for the Gipper." But in every other respect he was the dominant Olympic figure. His "new patriotism" was reflected in the crowds chanting "USA, USA" every time an American athlete competed. Most of all, the "resurgence of national pride" that the president wanted the country to feel was captured in the $6 million opening and closing ceremonies directed by Hollywood producer David Wolper. "The tone of the opening ceremony is going to be majesty," Wolper promised, and what followed were the most political Olympics since 1936. Wolper's plan to have an eagle take off from the west rim of the Coliseum and soar down onto the field during the playing of the national anthem was canceled at the last minute. But everything else went like clockwork. Church bells rang throughout the city. A plane wrote "WELCOME" across the sky, and a cast of nine thousand -- including 125 trumpeters, three hundred placard bearers, and eighty-four pianists playing "Rhapsody in Blue" -- performed on cue.

The peak in extravaganzas came two years later, on July 4, 1986, with the hundredth anniversary of the Statue of Liberty. It was the perfect Reagan moment, an occasion to match the politics of restoration with the restoration of a national monument. On opening night, as the faces of the president and his wife were superimposed on the image of the relit statue, he took the tribute in stride, as if such a blending of iconography were only natural. Later he spoke of his tax bill putting a smile on [Miss] Liberty, but here, as at his inaugural, the president knew that the best way to be effective was to play a role. The spectacle of Liberty Weekend, like that of the Olympics, was left to David Wolper to orchestrate. With a $30 million budget and no athletes to worry about, Wolper had few constraints. Television rights for the weekend went to ABC for $10 million. Millions more came from sponsors paying to use the statue in their advertising. Like the candy makers who carved a fourteen-foot chocolate replica of Liberty or the caterer who molded her likeness out of sixty pounds of chopped liver, Wolper was free to let scale dictate choice....The extravaganza's message was again unmistakable. To be American was to be powerful, and to be powerful was to be rich.

What about the homeless, whom Los Angeles police swept off the streets during the Olympics? Or the poor, whom the Statue of Liberty welcomed but who were not welcome at Liberty Weekend? "The social safety net for the elderly, the needy, the disabled, and the unemployed will be left intact," the president promised. But the crucial point was that such a safety net, like the safety net for the circus aerialist, was to be kept out of sight. The problem with our concern for the poor, both the Reagan administration and the culture of triumph held, was that in the past it had crippled them, In his influential 1984 book, Losing Ground, conservative Charles Murray of the Manhattan Institute described how, as a result of relaxed welfare standards and liberal court rulings, the 1960s had made it easier for the poor to get along without jobs and get away with crimes. For Ronald Reagan, the Murray view of poverty offered the perfect reason to cut back on aiding the poor. "Federal welfare programs have created a massive social problem," he insisted. "Government created a poverty trap that wreaks havoc on the very support system the poor most need to lift themselves out of poverty -- the family."

"Reagan made the denial of compassion respectable," New York governor Mario Cuomo complained. "He justified it by saying not only that the government wasted money, but also that poor people were somehow better off without government help in the first place." The country was, however, in no mood to listen to Cuomo or bother with figures showing that in the 1980s the living standard of the bottom fifth of the country dropped by 8 percent while that of the top fifth rose by 16 percent. Indeed, the kind of denial Reagan and Charles Murray had made respectable with regard to the poor was part of a much larger pattern of denial that was inseparable from the culture of triumph.

Irangate, the stock market crash of 1987, the scandals at the Environmental Protection Agency, the influence-peddling trials of White House aides Michael Deaver and Lyn Nofziger might easily have changed the country politically. But the culture of triumph made dwelling on such negatives a repudiation of what was best in America. We had gotten ourselves into trouble during the 1970s by imagining we were weak when we were not. There was no point in going through that again. In the president's words, "We've stopped looking at our warts and rediscovered how much there is to love in this blessed land."

A powerful counterculture might have challenged such a selective approach to events, but even at its best the counterculture of the 1980s found itself checked by the culture of triumph. The precedent set in 1980, when the mourning for John Lennon's Christmas-season assassination was quickly overshadowed by the first Reagan inaugural, continued throughout the decade. Two years after its installation, Maya Lin's elegiac, black granite Vietnam Memorial was sharing space in Constitution Gardens with Frederick Hart's bronze statues of three battle-weary infantrymen. In even less time, Bruce Springsteen's Born in the USA album, with its haunting portrait of a young vet trying to eke out a living in a declining industrial town, became the musical inspiration for Chrysler automobile's upbeat "Made in the USA" commercial.

Most important, the liberal tradition that might have provided the counterculture of the 1980s with a political base collapsed. When accused of being a liberal during the 1988 presidential debates, Michael Dukakis complained about being labeled, before declaring weeks later that he was a liberal in the tradition of Franklin Roosevelt and John Kennedy. But the damage was done. By the end of the second presidential debate, the liberalism of Dukakis and the Democrats lay exposed as a narrow proceduralism -- "scolding," Congressman Barney Frank called it -- that made upholding the law the remedy for everything from crime in the street to Irangate.

In the end the 1980s offfered no antidote for the cult of success which the culture of triumph made the centerpiece of the decade. When the public extravaganzas of the Reagan administration ended, the private extravaganzas of the super-rich replaced them. The excesses of the Bradley Martins' famous party of 1897, in which the Waldorf ballroom was done over to resemble Versailles at the cost of $400,000, were given new life. In the summer of 1989, Wall Street financier Saul Steinberg's $1 million fiftieth birthday party was not even the event of the season. That honor went to publisher Malcolm Forbes for a $2 million seventieth birthday party in Morocco. There he and eight hundred guests, flown from the United States on three jet airplanes, were entertained by six hundred acrobats, jugglers, and belly dancers, had an honor guard of three hundred Berber horsemen, and consumed 216 magnums of champagne in toasts.

"How do you defend it? I don't try to defend it," Forbes said of his party. A few years earlier, shortly before his conviction for insider trading, Wall Street arbitrager Ivan Boesky put the same sentiments in even blunter language. "Greed is all right, by the way," he declared in his 1986 commencement speech at the University of California Business School in Berkeley. "Greed is healthy."

....Those who gave Ronald Reagan and George Bush their overwhelming victories were not voting out of simple self-interest, especially in a year like 1984 when they were 54 percent of blue-collar workers, 59 percent of white-collar workers, and 57 percent of those with incomes between $12,500 and $24,999. They were voting for a culture they saw as hopeful and with which they identified, even when it failed to benefit them directly.

|